THIS A CRAZY ASS STORY

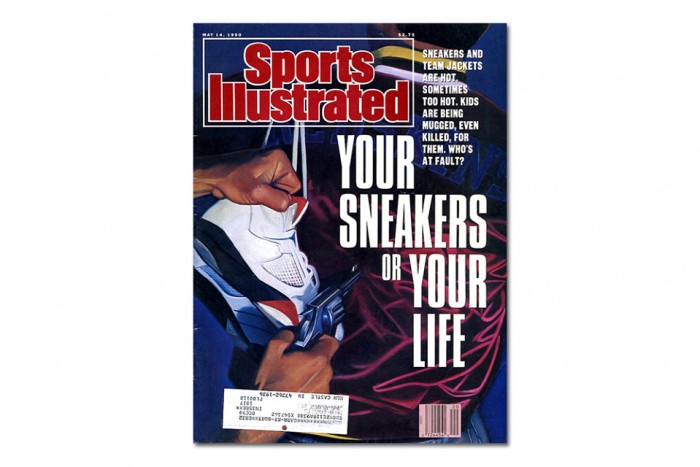

They found him – Michael Eugene Thomas – on May 2, 1989. He was 15. Strangled. Barefoot. Soon after, David Martin, a “basketball buddy,” would be charged with his murder whose motive was so horrifying that it sent ripples around the world and was brought to further national attention when Sports Illustrated and reporter Rick Telander published a cover story entitled “Your Sneakers Or Your Life” with the lede “sneakers and team jackets are hot, sometimes too hot. Kids are being mugged, even killed, for them. Who’s at fault?” That’s still a question the fashion world and the burgeoning brands with in-demand products face today. Yet, there was no pivotal moment or a collective decision that curbed the violence. Instead, we just came to accept that peoples nefarious activities were better viewed merely as criminal than that of offenses by those who let fashion dictate their motives as if the products themselves were illicit.

They found him – Michael Eugene Thomas – on May 2, 1989. He was 15. Strangled. Barefoot. Soon after, David Martin, a “basketball buddy,” would be charged with his murder whose motive was so horrifying that it sent ripples around the world and was brought to further national attention when Sports Illustrated and reporter Rick Telander published a cover story entitled “Your Sneakers Or Your Life” with the lede “sneakers and team jackets are hot, sometimes too hot. Kids are being mugged, even killed, for them. Who’s at fault?” That’s still a question the fashion world and the burgeoning brands with in-demand products face today. Yet, there was no pivotal moment or a collective decision that curbed the violence. Instead, we just came to accept that peoples nefarious activities were better viewed merely as criminal than that of offenses by those who let fashion dictate their motives as if the products themselves were illicit.

In the years following the murder of Thomas, a number of other slayings reached the national news for similar grizzly details, the victims ages, and the association with coveted fashion items. Notably, there was Dewayne Williams Jr. who was stabbed to death on December 2, 1992 for his Raiders jacket – and a slew of other Raider-centric murders all related to the piece of outerwear and the adoption of professional sports emblems as a street gang allegiance identifier.

It became such a national epidemic in fact that the NFL’s chief of retail licensing, Frank Vuono, told The New York Times, “We don’t bury our heads in the sand. We are very in tune with it.” Raiders executive assistant Al LoCasale told The Baltimore Sun, “I got a lot of calls from parents, saying they bought their child a Raider hat and the school said they couldn’t wear it because it’s identified with gangs. We share their concern. There’s a need to find an answer to the problem that’s not as simplistic as just taking the hat or jacket off.”

While national attention shifted from that of “fashion-centric” crimes to merely the reporting of youth violence as a whole, many assumed that the violent phenomenon from the ’90s disappeared as if a sartorial fad. Not only has it continued, it’s hardly faded. Society may have grown wiser regarding gangs and their usage of certain logos and colorways, but the “dangerous enthusiasm” circling the growing streetwear sector and the lively resale market suggests that we’re destined for an upswing in violence.

Air Jordans Then vs. Air Jordans Now

Prosecutor Mark Vinson – who handled the case of the 1989 slaying of 16-year-old Johnny Bates who was shot to death in Houston by 17-year-old Demetrick Walker after Johnny refused to turn over his Air Jordan high-tops – said, “It’s bad when we create an image of luxury about athletic gear that it forces people to kill over it.” Michael Jordan responded to the news of the murders by saying “everyone likes to be admired, but when it comes to kids actually killing each other, then you have to reevaluate things.”

But have we?

Air Jordans continue to dominate the sneaker world despite Michael Jordan retiring from the NBA in 2003 and is a testament to the shoe transcending mere apparel and representing what a wearer wants to make outwardly known about him/herself. According to ABC, opponents of the marketing strategy (relating to limited quantity releases) suggest that “it has caused 1,200 deaths per year nationwide.” In the last five years alone, Air Jordan-related murders and other bouts of violence include the slaying of Joshua Woods, a stabbing in New Jersey, and a number of high-profile bouts of chaos reminiscent to the events of the Supreme x Nike Air Foamposite One release in New York City. In an article in the Washington Post, Marshal Cohen, chief retail analyst at the NPD Group, said the shopping frenzy around the shoe is arguably more important than the number of dollars Nike will make selling it. “As a shoe by itself, it’s moderately important,” Cohen said. “But as a marketing concept and a retailing partnership? Genius.”

The biggest change between Jordans then and Jordans now are astounding numbers that suggest Nike has no plans of switching strategies. As of 2009, the Jordan brand had a 10.8 percent share of the overall U.S. shoe market, which made it the second biggest brand in the country and more than twice the size of adidas’ share. Additionally, three out of every four pairs of basketball shoes sold in this country are Jordan, while 86.5 percent of all basketball shoes sold over $100 are Jordan.

Resale as a Career

Since the slaying of Michael Eugene Thomas in 1989, the size of the athletic shoe market has more than doubled to $21 billion USD a year in the United States alone. Nestled amongst that staggering number is an ever-growing pocket of capitalists who seek full-time employment by simply continuing the vicious cycle that is buying and reselling hot commodities. Matt Powell, a retail analyst with SportsOneSource, says Nike actually encourages this by setting prices lower than what the market will bear. I think they always try to keep the supply below demand level,” Powell said. “They want their shoes to sell out in a relatively short period of time, because that creates excitement for the next one around.”

Josh Luber, founder of Philadelphia-based Campless.com – a resell-tracking data company – estimates that in terms of secondary sales on eBay, sneakerheads accounted for approximately $200 million in 2013. “In dollars and cents, sneakerheads make up a tiny portion of the industry,” Powell told the Boston Globe, “but their fervor certainly creates heightened interest in shoes.”

It should be noted that the resale market isn’t merely a product of the rise of the Internet and the social media channels that sprung out of one’s ability to instantly interact with those with a similar interest. As far back as 1998 there’s coverage of a “hot resale market for fetid old sneakers.” The major difference in the coverage is that the resale market was purely for wear as opposed to profit, with Sports Illustrated noting, “The vast majority of the consumers are not the among the legion of sports memorabilia collectors who covet Michael Jordan’s jockstrap but rather are Japanese fashion Brahmins with an eye for camp who actually wear what they purchase.”

Violence and Brand Response

The most notable case of a changing of philosophies as it relates to high-profile releases is undoubtedly the Air Yeezy II “Red October.” While the release had many looking at the strained relationship between Kanye West and Nike as a source of the unexpected drop, perhaps Nike is finally starting to understand that demand will be met no matter how the supply is unleashed. While a move to a more technical strategy seems to eliminate potential person on person confrontations, the “cold” nature of the announcement and subsequent follow-through registers like a fresh slop deposit at a Las Vegas buffet.

Of course, foresight can’t always be achieved. Instances arise that force a brand to act no matter the financial implications. As was the case back in 2008 when Nike was forced to withdraw the Air Stab from the market following an increase in fatal knife attacks in the UK. The running shoes were originally sold in 1988 but a limited edition retro range was relaunched in 2006, carrying the phrase “Runnin’ ‘n’ Gunnin”‘ on one version. A company spokesman said at the time, “Given the current climate we have withdrawn the shoe indefinitely from Nike’s own stores in the UK. While it may be an unfortunate coincidence timing-wise, given current problems regarding knife crime, we completely reject the idea that we are in any way condoning or encouraging the issue of knife usage.”

Michael Eugene Thomas

When you read or hear about his death, it’s still jarring. “Killed for his shoes” sounds like the type of short burst fiction that is often attributed to Ernest Hemingway. There’s no refuting the facts that his killer, James David Martin, had made off with his pair of Jordans. But was that the true motive?

James David Martin would be released seven years after killing Michael Eugene Thomas. He would kill three more people – tied to three separate incidents involving the strangulation on women.

In the end, the shoes Martin stole didn’t even fit him.

Alec Banks is a Los Angeles-based writer who can be found @smart_alec_

Image Credits: Sports Illustrated May 1990, In My Blood by Cristiano Siqueira