“To have and to hold” is a line a couple utters to one another moments before someone of their choosing unites them in holy matrimony. It’s a time honored tradition for love birds. Years ago, this was a phrase that could apply to how music lovers satiated their sonic desires – thus ponying up the 14 or so dollars to get a tangible piece of music – whether it was a piece of vinyl or a CD. Remember cover art you could hold? Remember liner notes with lyrics – that to a teenager registered like the gospel as delivered at the pulpit by those like Cobain and Smalls? Those days aren’t quite gone, but as more and more listeners sacrifice sound quality for ease at which one can pick and choose as if an OCB-LP buffet, it’s clear that burning a CD isn’t quite as Earth-shattering a statement as burning a bra was in the ’60s. But have we turned a corner? Is the ability to listen at will a substitute for actually owning an album – and if so, does that mean piracy has been pushed overboard?

#splash

In their own words, “When Spotify was founded in 2006, one of the original goals was to beat piracy at its own game and offer the music consumer a superior and legal alternative.” They contend that there’s no correlation between high streaming numbers and low tangible sales based on a 2012 study by Will Page, Director of Economics for the company, who concluded, “The most popular album on Spotify had the highest (best) sales to piracy ratio. One Direction’s Take Me Home was available on Spotify on its release day; it had the highest weekly Spotify stream count and sold the second largest volume of albums in its release week.” Conversely, he contends that, “There is no evidence that holdouts (those who don’t make their albums immediately available) sell more. Rihanna’s Unapologetic entered the Dutch charts at number 6 and fell to number 11 in its second week – and suffered 3-4 times as much piracy per sale as Take Me Home.” While the sample size is small, there’s no denying that they’re sending a loud-and-clear message to artists: It’s no longer “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em,” but rather, “we can beat ‘em, so join us.”

#newrules

Beyoncé’s self-titled album sold 828,773 digital copies worldwide in just three days (617,213 moved in the U.S.) – thus becoming the fastest selling album ever on the iTunes Store. This comes in the wake of a musical year where we got more “out of the blue” material from the likes of Justin Timberlake and Jay Z. Music-industry consultant Mark Mulligan told TIME, “There is a growing trend of big artists doing something a bit different digitally, knowing it will get an amount of media interest. The newness of the tactic is its own benefit; there’s so much more new music than there are dollars being spent on music that it’s necessary for an artist to do something to break through the background noise. There’s also the issue of leaks which is a factor Beyoncé’s team pointed to in describing the Beyoncé release strategy as a ‘fully designed preventative plan.’”

Classic rockers Pink Floyd penned an op-ed for USA Today on its critique of streaming apps and their revenue model, saying, “Internet radio companies are trying to trick artists into supporting their own pay cut. A business that exists to deliver music can’t really complain that its biggest cost is music. You don’t hear grocery stores complain they have to pay for the food they sell. Netflix pays more for movies than Pandora pays for music, but they aren’t running to Congress for a bailout. Everyone deserves the right to be paid a fair market rate for their work, regardless of what their work entails.” So where does Spotify stand?

Spotify pays out the majority (approaching 70%) of ALL of their revenue (advertising and subscription fees) to rights holders: artists, labels, publishers, and performing rights societies (e.g. ASCAP, BMI, etc.). In just three years since launching, Spotify has paid out over $500 million USD in royalties. In general, however, Spotify pays royalties in relation to an artist’s popularity on the service. For example, they will pay out approximately 2% of gross royalties for an artist whose music represents approximately 2% of what our users stream. Thus, a popular song or album can generate far more revenue for an artist over time than it historically would have from upfront unit sales.

#differentstrategies

Several artists in the “digital” era have opted to either have fans pay what they want (Radiohead), or pay an ordinate amount of money ($100 dollars) for a project like Nipsey Hussle did for his mixtape, Crenshaw. While Radiohead’s In Rainbows was a financial success and Hussle’s pop-up shop sold $100,000 USD worth of his tape, in the case of Radiohead, a study by the American Marketing Association asserts that when given the opportunity to decide what to pay, “consumers will exploit their control and pay nothing at all.” Whether it’s stealing the music or buying it, Hussle’s method is the only contemporary strategy that suggests it benefits the artist when we the listeners demand freedom of choice in what we consume and what we pay.

#diagnosis

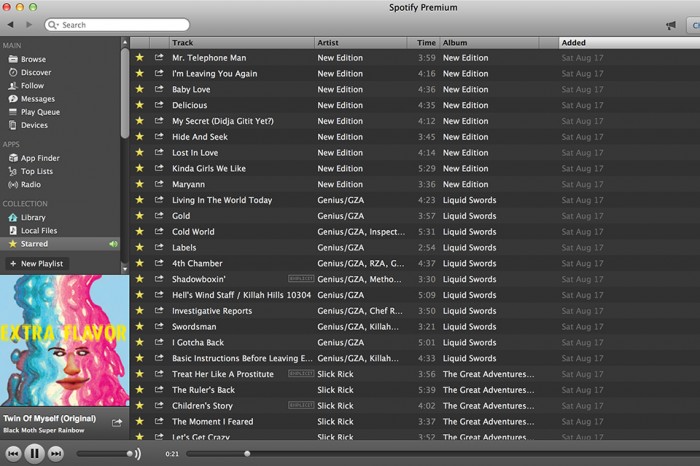

When Spotify announced that it would be bringing an enhanced “free” model to Android and iOS users, Spotify CEO/Founder Daniel Ek told reporters, “I truly believe we’re turning a corner on this one. For the first time in more than a decade, there’s a feeling that the whole music industry is stabilizing now, and maybe even getting back on its feet. And that goes for artists too.” In the weeks since bridging the gap between premium accounts and Johnny Come Lately’s, the company has had four times the amount of downloads than normal – indicating that while Spotify is still behind Pandora in terms of global users (24 million active users in 55 markets worldwide vs. 72.4 million active listeners and more than 200 million registered users), it suggests that there is a genuine excitement for getting the auditory golden ticket.

I like to think of Spotify as an “audiobiotic.” Meaning, it’s a fix to a much larger problem that still continues to invade platinum and gold sales because when there’s a wi(fi)ll there’s a way. As Ek has said, “access has become the leading model for enjoying music” – and with the power of the Internet, the door is always unlocked. Consider this medical tidbit – Antibiotic resistance occurs when antibiotics no longer work against disease-causing bacteria. If Spotify/streaming is our only viable means to eradicate a problem, eventually those that use them will no longer feel its benefits. Slowly but surely streaming services won’t “have the music I like,” or any number of other excuses, and we’ll be right back where we started. The patient is indeed having a miraculous turn around thanks to streaming services, but as Kurt Cobain once said, “If it’s illegal to rock and roll, throw my ass in jail!” To him, the music and the lawless behavior is one in the same.

Alec Banks is a Los Angeles-based writer who can be found @smart_alec_